Japanese sake is a unique alcoholic beverage, and it is deeply rooted in the culture and climate of Japan.

Contents

- Discovering Sake

- Sake Brewing

- Hot Sake & Cold Sake

- Seimai (Rice Polishing)

- Paring Sake and Food

- How to use Japanese Sake for cooking?

Discovering Sake

Its tradition and the future

Japanese sake can be argued that it’s an expression of the Japanese people and their history. On the other hand, more and more people in other parts of the world are discovering sake, and its popularity is growing ever more rapidly. What makes sake so unique is that it is both a very Japanese product at its core while becoming a worldwide phenomenon? It is surely not only the flavor and the history of craftsmanship. It is also about the freedom it offers as a new kind of alcoholic beverage that was, until recently, unknown in the western world.

Japanese sake can be argued that it’s an expression of the Japanese people and their history. On the other hand, more and more people in other parts of the world are discovering sake, and its popularity is growing ever more rapidly. What makes sake so unique is that it is both a very Japanese product at its core while becoming a worldwide phenomenon? It is surely not only the flavor and the history of craftsmanship. It is also about the freedom it offers as a new kind of alcoholic beverage that was, until recently, unknown in the western world.

The origin of sake is shrouded in mystery, and it is not known when or where it started. It is clear, however, that people already enjoyed sake throughout Japan in the Asuka period in the 6th century. The sake of that time had less alcohol content – it took hundreds of years more to perfect the brewing method – but the concept was already there. In this way, it was similar to the sake that we know today, made from rice, water, and koji mold.

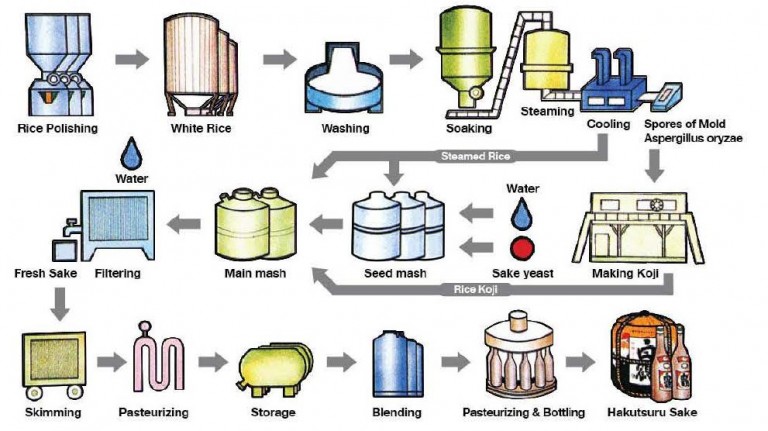

The sake brewing process is unique, and is different from alcoholic beverages such as wine or beer. The most distinguishing aspect of the brewing process is what is known as the multiple parallel fermentation of rice. While wine is produced in one step by simply fermenting grape sugars, sake is produced by fermenting rice to convert it into sugars and alcohol simultaneously. A special mold called Aspergillus oryzae is mixed with steamed rice and begins the fermentation process, resulting in what is known as koji, the fermented mixture of rice and mold. In the same batch, water and yeast culture are added and mixed with the koji, kickstarting the parallel process of fermentation. If the process is successfully controlled, the koji keeps breaking down the rice into sugars and other nutrients, which are then, in parallel, gradually consumed by the yeast to produce alcohol. The process may take several weeks to finish.

Master of Sake, Toji

The master sake brewer that oversees the whole process is known as the Toji. Interestingly, the Toji is seldom the owner of the Sake brewery but is rather a specialist craftsman employed by the brewery. Toji is a title traditionally passed down from father to son, just as most breweries have been passed down from owner to child. If the owner is the businessman, the Toji is the artist. He is the samurai to the Shogun. Rather than the owner, it is the Toji who tends to dictate the taste and the direction of the brewery’s sake. For this reason, Tojis are highly regarded in Japanese culture, where craftsmanship is often praised more highly than ownership.

The master sake brewer that oversees the whole process is known as the Toji. Interestingly, the Toji is seldom the owner of the Sake brewery but is rather a specialist craftsman employed by the brewery. Toji is a title traditionally passed down from father to son, just as most breweries have been passed down from owner to child. If the owner is the businessman, the Toji is the artist. He is the samurai to the Shogun. Rather than the owner, it is the Toji who tends to dictate the taste and the direction of the brewery’s sake. For this reason, Tojis are highly regarded in Japanese culture, where craftsmanship is often praised more highly than ownership.

The terrain and climate of Japan are well suited to the creation of sake, and it is possible that sake could not have been born without these particular environmental factors. Japan is comprised of mountainous islands with a lot of rain and moisture, where pure, soft water – the often underestimated key ingredient for sake – is abundantly available. Its distinct four seasons with wet, hot summers allow rice to grow in abundance, while the cold, dry winters are perfect for the brewing process. Long before mechanical air-conditioning was invented, Japanese sake makers found that the chilling temperature of the winter months created the ideal setting for brewing. So workers gathered in winter and worked in the early morning hours before sunrise, when the temperature is the coldest. This was the practice for making high quality sake.

The terrain and climate of Japan are well suited to the creation of sake, and it is possible that sake could not have been born without these particular environmental factors. Japan is comprised of mountainous islands with a lot of rain and moisture, where pure, soft water – the often underestimated key ingredient for sake – is abundantly available. Its distinct four seasons with wet, hot summers allow rice to grow in abundance, while the cold, dry winters are perfect for the brewing process. Long before mechanical air-conditioning was invented, Japanese sake makers found that the chilling temperature of the winter months created the ideal setting for brewing. So workers gathered in winter and worked in the early morning hours before sunrise, when the temperature is the coldest. This was the practice for making high quality sake.

The sake brewing method has evolved considerably in the last several decades, with simply stunning results. We now have a whole variety of sake, from those made for everyday consumption to those meant to be appreciated at the finest dining occasions. There is very sweet as well as very dry sake. There is Genshu, the undiluted sake with higher alcohol content; Nigori, the cloudy unfiltered sake; and even sparkling sake. These sake varieties are gaining wide acceptance among casual sake drinkers.

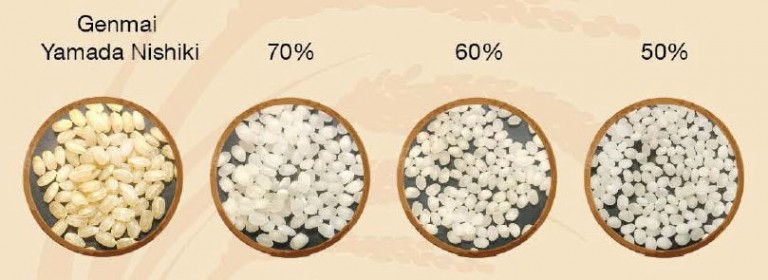

The craftsmanship of the Tojis, however, is expressed to its fullest in Ginjo sake. There are several grades of Ginjo sake, with Junmai Daiginjo being the pinnacle of Ginjo sake. It is also arguably the purest form of sake. This is sake where the rice is polished to less than 50% of its original size. Some Tojis boldly choose to polish the rice even further to a mere 35%! When the rice is shaved this close to its core, it results in leaving only the best part of the starch, and the reduced size helps it to fully ferment. Surprisingly, it was not until the early part of the twentieth century that the Tojis discovered that making sake from such highly polished rice produces a unique aroma, called Ginjo-ka. It is often described as fruity, invoking oranges and apples. This pleasant aroma completely distinguishes the Ginjo class sake from ordinary sake. Moreover, the detailed nuances of the flavors differ significantly from brewery to brewery, and from Toji to Toji. This wide range of Ginjo-ka, which often cannot be reproduced, adds depth and mystery to the enjoyment of sake. Once learned, the fragrant presence of the Ginjo-ka is unmistakable. For some connoisseurs, sake means Ginjo class sake.

The craftsmanship of the Tojis, however, is expressed to its fullest in Ginjo sake. There are several grades of Ginjo sake, with Junmai Daiginjo being the pinnacle of Ginjo sake. It is also arguably the purest form of sake. This is sake where the rice is polished to less than 50% of its original size. Some Tojis boldly choose to polish the rice even further to a mere 35%! When the rice is shaved this close to its core, it results in leaving only the best part of the starch, and the reduced size helps it to fully ferment. Surprisingly, it was not until the early part of the twentieth century that the Tojis discovered that making sake from such highly polished rice produces a unique aroma, called Ginjo-ka. It is often described as fruity, invoking oranges and apples. This pleasant aroma completely distinguishes the Ginjo class sake from ordinary sake. Moreover, the detailed nuances of the flavors differ significantly from brewery to brewery, and from Toji to Toji. This wide range of Ginjo-ka, which often cannot be reproduced, adds depth and mystery to the enjoyment of sake. Once learned, the fragrant presence of the Ginjo-ka is unmistakable. For some connoisseurs, sake means Ginjo class sake.

Sake in the U.S.

Here in twenty-first century America, sake is enjoying unprecedented recognition and popularity. As sushi and other forms of Japanese foods made inroads into American menus, people started so realize that the flavor of sake complements these dishes best. Western foods, especially American foods such as steaks, tend to be high in animal protein, which goes well with tangy wine or other alcoholic beverages with a lot of punch to counter the strong taste of meat. Japanese foods, on the other hand, are often lower in protein and high in starch; which calls for softer, more fragrant alcoholic drinks, even with some sweetness.

The trend for sake consumption is now spreading internationally beyond Japan and America. We sense that this is only the beginning, and that a new generation of young people from all over the world are discovering sake and making it part of their own culture. We hope that this popularity will in turn stimulate the Tojis and the breweries in Japan to create even more distinctive and delicious sake for generations to come. We are discovering that, in sake, Japanese tradition is meeting the world and growing ever stronger.

Sake Brewing

The making of sake is one of the most advanced and complicated fermentation methods in the world. Two fermentations take place in one tank at the same time. One is the fermentation from starch to sugar, the other is the fermentation from sugar to alcohol.

Sake Making Process

Hot Sake & Cold Sake

There is perhaps no alcoholic beverage other than “sake” that can be enjoyed at a variety of temperatures ranging from hot to cold. The temperature you choose depends on the type of sake, the time and the season.

There is perhaps no alcoholic beverage other than “sake” that can be enjoyed at a variety of temperatures ranging from hot to cold. The temperature you choose depends on the type of sake, the time and the season.

The traditional way to drink sake is to serve it heated, called “kan-zake or hot sake”, warmed. On a chilly evening, there is nothing better than hot sake. To heat up your sake, pour it into a small porcelain jar, then put it in a saucepan of hot water to heat for about 3 minutes. The proper temperature is from 100°F to 120°F, depending on one’s taste. But remember, kan-zake should just be warmed but never boiled.

Another way of serving sake is cold or chilled. The temperature should be around 46°F. We brew our “draft sake” to be slightly dry and fruity, and it can be served directly from the refrigerator. When the weather gets hot, cold sake is very refreshing, and its subtle aroma gives a richness of taste.

Another way of serving sake is cold or chilled. The temperature should be around 46°F. We brew our “draft sake” to be slightly dry and fruity, and it can be served directly from the refrigerator. When the weather gets hot, cold sake is very refreshing, and its subtle aroma gives a richness of taste.

Some people also enjoy sake served at room temperature or on the rocks. You can enjoy sake at a wide range of temperatures and each temperature brings out a variety of sweet/dry changes. Here are a list of different temperatures of sake:

Kanzake (燗酒): Hot or warm, ‘sake’

Joukan (上燗): Hot ‘sake’ (around 122°F)

Nurukan (ぬる燗): Warm ‘sake’ (around 104°F)

Hitohadakan (人肌燗): Lukewarm, ‘sake’ (around 95°F)

Jouon (常温): ‘Sake’ served at room temperature

Reishu (冷酒): Chilled ‘sake’ (41°F to around 46°F)

Seimai (Rice Polishing)

“Seimai” the process of removing the outside part of rice.

This is because fats and proteins (among other things) that cause the “sake” quality to degrade are located on the outer part of the rice. The degree of polished rice is expressed with the “rice polishing ratio”; a rice polishing ratio of 70% means that 30% of the outside is removed.

| Name | Ricce Polishing Ration (Remains) | Description | How to enjoy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Junmai Dai Ginjo-shu(sake) 純米大吟醸酒 |

Less than 50% | High-end, sophisticated sakes. Very delicate and skilled techniques are necessary for brewing. Using a special yeast, they have been fermented for a longer term than usual sakes. Characterized by their fruity aroma and smooth taste. | Chilled , at room temperature, lukewarm. |

| Junmai Ginjo-shu(sake) 純米吟醸酒 |

Less than 60% | ||

| Junmai shu(sake) 純米酒 |

Less than 70% (Our regulation) | Pure rice sake. Only Rice, rice koji & water are used for the ingredients. Characterized by its rich rice flavor and mellow taste. | Enjoyable at any temperature. Rich taste is emphasized at warm/hot. |

| Junmai Namachozou-shu(sake) 純米生貯蔵酒 |

Less than 70% (Our regulation) | Fresh style sake. It gains its fresh, refined taste from being brewed and aged for 1 month in a cool state at about 41 °F before bottling. This sake is pasteurized only once at bottling in order to retain its fresh taste. Characterized by its light, fresh and smooth taste. | Chilled |

| Junmai Nigori-Sake Unfiltered or Coarse-filtered Sake 純米にごり酒 |

Less than 70% (Our regulation) | Creamy sake passes through a mesh and coarsely filtered. This process gives sake a refreshing aroma, natural sweetness and smooth aftertaste. | Chilled |

Paring Sake and Food

Sake goes well with traditional and contemporary tastes. The flavor of sake has developed along with traditional Japanese foods such as sukiyaki, tempura, sushi and tofu. Whenever you eat these dishes, treat yourself to a glass of sake. The flavors enhance each other making the food and sake taste better.

Sake goes well with traditional and contemporary tastes. The flavor of sake has developed along with traditional Japanese foods such as sukiyaki, tempura, sushi and tofu. Whenever you eat these dishes, treat yourself to a glass of sake. The flavors enhance each other making the food and sake taste better.

Sake may also be used in the preparation and cooking of Japanese and Western meals. But, you don’t need to prepare special Japanese food to go with sake, just drink it as same as you would wine or beer, at a barbecue or a regular meal. It also goes well with potato chips, cheese, peanuts, and other light snacks. Warm, cold or “on the rocks”, try sake with your next meal. Generally speaking, rich sake is good with rich or heavy-flavored foods. such as fatty tuna, salmon, sea urchin, eel, or beef steak. Light sake is good with light taste foods such as squid, octopus, white fish, seafood salad, poke, and seafood pasta. Sweet sake can be enjoyed as dessert sake or good with spicy foods such as spicy tuna, Thai, Mexican, and Korean foods. Kanpai!

How to use Japanese Sake for cooking?

Sake sangria Recipe

Sangria is a drink where red wine is mixed with fruit juices and pieces of fruit. Here we have created a Japanese-style version by combining sake and yuzu juice.

Sangria is a drink where red wine is mixed with fruit juices and pieces of fruit. Here we have created a Japanese-style version by combining sake and yuzu juice.

Ingredients (Serves 4)

4 cups sake

2 cups yuzu juice

2 cups simple syrup (equal parts of water and sugar are boiled and cooled)

Fruits, to taste

Cooking Directions

- Prepare the simple syrup and let it cool.

- Cut fruit into bite-size pieces.

- Mix all the ingredients. Chill in the refrigerator.

Sake Manju Recipe

Manju is a popular wagashi, a traditional Japanese confection. Here, we have created sake manju where you can enjoy the aroma of sake with the sweetness of manju.

Manju is a popular wagashi, a traditional Japanese confection. Here, we have created sake manju where you can enjoy the aroma of sake with the sweetness of manju.

Ingredients (Serves 12 pieces)

3 tbsp. sake-kasu (sake lees)

1.5 cups yellow soft sugar

3/4 cup sake

2 cups cake flour

1 tbsp. baking powder

Wheat flour (for dusting, as needed)

Koshian (mashed red bean paste, as needed)

Cooking Directions

- Divide the koshian into 12 parts and shape into balls.

- Combine sake kasu, yellow soft sugar and sake.

- Combine the cake flour and baking powder with Step 2 and knead thoroughly.

- Divide Step 3 into 12 equal parts and shape into balls.

- Wrap koshian from Step 1 into the dough of Step 4 and wrap.

- Steam the manju balls from Step 5 in a steamer for about 20 minutes.